Monument of States Kissimmee Florida A History

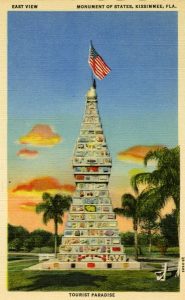

The Monument of States is located just south of downtown Kissimmee, Florida, near the intersection of Lakeview Drive and Monument Avenue.

The Monument of States was the brainchild of Dr. Charles W. Bressler-Pettis. As Joy Dickinson has written about Bressler-Pettis, “…one Central Floridian was galvanized to express the nation’s unity in a singular, towering vision: a monument in his winter home, Kissimmee, that would express the bond between states and continue to inspire tourists to stop, look up and wonder.” (Patriotism)

Monument of States

The Monument of States as it currently stands has several origin stories. Some claim it dates back to 1935 (Doctors Love) while most state that it was conceived in response to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. (National Register, Patriotism)

Dr. Charles W. Bressler-Pettis was an active member of the Lions Club and Kissimmee All-States Tourist Club and in the early 1940s partnered with J. C. Fisher to design a monument as a symbol of American unity in a time of war.

To learn more about the war that inspired this incredibly unique and beautiful monument, I recommend a subscription to World War II magazine. World War II magazine covers every aspect of history’s greatest modern conflict with vivid, revealing, and evocative writing from top historians and journalists

Promotion for the monument began immediately. By the end of December 1941, an Honor Role of Cement Donors had been established. Here, individuals and businesses who supplied a bag of concrete were thanked for their contribution. A pamphlet was produced listing 507 concrete donors. (National Register)

Groundbreaking occurred on January 11, 1942 with the cornerstone being set in place. Volunteer labor, much of it coming from the Kissimmee All States Tourist Club, kept the project in motion. Bressler-Pettis collected rocks from donors across the country for use in the monument. Bressler-Pettis also supplied many rocks from his own travels. He wrote letters to state governors asking for representative rocks. President Franklin D. Roosevelt contributed a stone from his Hyde Park, New York residence.

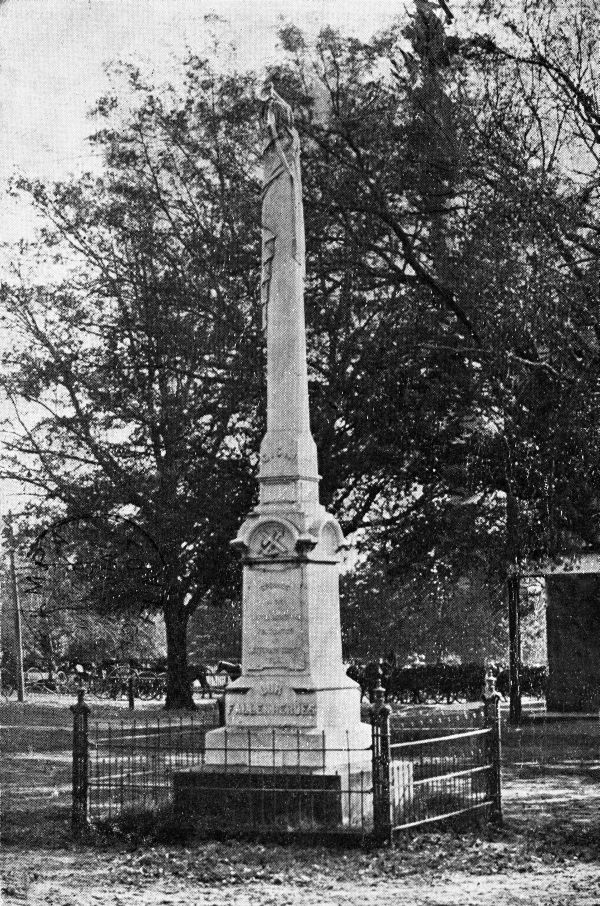

Once complete, the monument consisted of more than 1,500 stones from the then 48 states and 21 countries. It contained 21 tiers and reached 50 feet tall. The eagle atop the monument has a wingspan of six-feet. The base of the monument measures sixteen square feet and the top tier is only two and one half square feet. The foundation for the monument is three feet thick, twenty-two square feet, and weighs approximately 100,000 pounds. (National Register, Patriotism)

United States Senator Claude Pepper was on hand for the monument dedication on March 28, 1943. In the years since the monument has been the location of many ceremonies including a 50-year celebration on March 28, 1993 when officials placed a time capsule at the monument. The capsule will be opened on the 100th anniversary of the dedication.

Cultural Importance

The Monument of States represents a time in Florida tourism before the onslaught of theme parks and mass commercialization. The effort to create this monument brought together a community toward a common goal in a way that cartoon characters and comic book heroes never will.

For those interested in the significance of this monument to visitors, there are seemingly dozens of different postcard images of the Monument of States. This collection of images is important first, in placing the monument in time but also in documenting its early appearance. The diversity of images and the often handwritten messages sent home, show the impact the monument had on visitors. They felt this was an image worthy of sharing with the folks “back home.” In the era before social media, postcards were a convenient way of “tagging” where you were for your friends to follow.

In the years before Disney, those days of the road trip, Stuckey’s, “are we there yet,” and the roadside attraction, the Monument of States served as a tourist draw. In describing the monument and it’s relevance, the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form states, “It retains integrity of design, materials, workmanship, feeling and association with the early history and tourism efforts in Kissimmee, and continues to serve as a draw for both residents and visitors alike.” (National Register) The monument was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places in December 2015.

Dr. Charles W. Bressler-Pettis

Just who was Dr. Bressler-Pettis? Charles was born on February 12, 1889 in Grant City, Missouri to parents Manuel and Nellie A. Bressler. When or why Charles changed his surname to Bressler-Pettis is unknown. We do know that Pettis was his mother’s maiden name. The first known recorded use of this new name is on a 1922 passport application. (Osceola History)Young Charles was encouraged to become a medical doctor. At the urging of his family, after graduating from the University of Missouri he attended Harvard Medical School, graduating in 1917 and served his internship in Boston.During World War I Charles served in the British army medical corps before joining the United States army medical corps later in the fight. During the war Charles visited a wealthy uncle who was living in Nice, France at the time. After the war he returned to France where he became the personal physician for his uncle. Charles was to receive a large, lifetime income from the estate of his uncle.After returning to the States, Charles met, and married, Laura Mead. After their January 1927 wedding they embarked on a long honeymoon, logging over 78,000 miles by automobile.

Charles suffered a fatal heart attack while already in the hospital, on May 12, 1954. It is often repeated that Bressler-Pettis’s ashes are buried at the Monument of States. There is some truth to this story. After Charles’s death, his wife made request of the Kissimmee City Commission to be allowed to inter Charles’ ashes at the base of the Monument of States; a request that was approved by special ordinance. It appears however that Mrs. Bressler-Pettis may have reconsidered. The website, Findagrave, shows a listing for Charles W. Bressler-Pettis in Grant City Cemetery, in Grant City, Missouri, the city where Charles was born. (Findagrave, Osceola History) Both stories are true. I have found reference that part of his ashes were buried in each location. This seems like a reasonable answer based upon the City Commission going to the trouble of amending local ordinances. (Memorialogy, National Register)

Sources:

“Doctors Love of Area Fueled Drive for Monument.” Orlando Sentinel. July 22, 1990.

Findagrave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14214087/charles-w-bressler-pettis

Memorialogy. https://memorialogy.com/pages/entries/entries.php?post=n112

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.

Osceola History. https://osceolahistory.org/charles-w-bressler-pettis-the-bearded-man/

“Patriotism After Pearl Harbor Fueled Creation…” Orlando Sentinel. December 12, 2021.

Sandler, Roberta. A Brief Guide to Florida’s Monuments and Memorials. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.