Sands Fish & Oyster Company Florida Historic Marker

The Sands Fish & Oyster Company two-sided Florida Historic Marker can be found in Port Orange, FL and is accessed through Riverwalk Park, located on the east side of US1 (Ridgewood Avenue).

Florida Marker Program

The Florida Historical Marker Program is one of the Division of Historical Resources’ most popular and visible public history programs. It is designed to raise public awareness of Florida’s rich cultural history and to enhance the enjoyment of our historic sites by citizens and tourists. These markers allow us to tell the stories of the places and people who created the Florida that we all enjoy today, by identifying the churches, schools, archaeological sites, battlefields and homes that represent our past.

If you wish to learn more about this state program, including qualifications, how to apply, the application, costs, and more, please use THIS LINK.

Side One

Side One

The Sands Fish & Oyster Company supplied oysters to markets and restaurants up and down the Atlantic Seaboard from 1916 until 1955. Founded by William Sands, Sr., the company earned Port Orange, Florida, the title of “Oyster Capital of the World” by harvesting fresh, delicious oysters known far and wide. In addition to oysters, the company supplied clams, fish, and shrimp. Sands managed oyster leases along the Halifax River as far south as New Smyrna Beach and as far north as St. Augustine. Before starting his company he had worked as a bookkeeper for Daniel DuPont’s Port Orange Oyster Company. Originally located just north of Herbert Street along Halifax Drive, the Sands oyster house moved one block north to the corner of Ocean Avenue and Halifax Drive in the 1930s. In exchange for use of City of Port Orange property, the company provided the city with oyster shells for local roads. As the business grew, the oyster house expanded eastward over the river on pilings. Harvesting an average of 500 gallons of oysters per week, the company reached a high mark of 905 gallons during one week in 1943. Packed in gallon siz metal cans, the oysters were shipped out by truck.

Side Two

Side Two

A mainstay of the Port Orange business community, the Sands Fish & Oyster Company provided numerous jobs. Workers traveled from New York and Georgia to work the eight-month oyster season. During the off season, workers replenished the oyster beds and fished the river. For each gallon of oysters shucked, workers received a token known as a “Sands Dollar” that could be turned in for pay or used in local stores. In 1947, William Sands, Sr., passed away and his wife Mabel Sands and her son William Sands, Jr., took over the company. Success of the oyster business continued, but the water quality of the river declined after the construction of the second Dunlawton Bridge in early 1951. The bridge’s earthen causeway design, known locally as the “Port Orange Dam,” restricted the water’s tidal flow. Contaminants from septic tanks coupled with restricted flow raised bacterial levels in the river enough to end oyster harvesting. Sands Fish & Oyster remained in business selling fish, smoked mullet, clams, shrimp, and oysters that were supplied from other parts of the state. Mabel Sands sold the company to Fred and Martha Downing in 1956. The Downings continued the fish and shrimp market until 1961.

A Florida Heritage Site

Erected by the Port Orange, The City of Port Orange, and the Florida Department of State

F-851

2015

Comments About the Marker

As is often the case unfortunately, these markers do contain errors and the information should be confirmed independently. The text is often not written by historians, or many times even folks with any level of historical knowledge. At the state level, the details are not reviewed, rather, they are trusting that the writers and sponsors have done their research properly. There are some requirements during the submission phase. The review committee will only catch glaring errors of fact or omission. They are more used for stylistic edits and program consistency. They are not experts in every facet of local history.

Please note the unusual language in the “erected” notation at the bottom of the marker. There is definitely something missing. Whether this was submitted in this manner and missed during editing or was a manufacturing error I am unsure.

Sands Fish & Oyster Company founder, William Edward Sands, Sr. passed away on February 4, 1958 at the young age of 59. The historic marker incorrectly lists his death year as 1957. An online memorial for Sands, Sr. can be found HERE. In addition to confirming his death date on the memorial site, I have confirmed the 1958 date through newspaper obituaries and government death records.

William Edward Sands, Jr., who took over and ran the market for several years passed away in 2014 at age 93. An online memorial for Sands, Jr. can be found HERE.

I was able to verify that the Downings received a transfer of the property lease from Ms. Sands in July 1956. I have been unable to verify when the Downing family closed the business.

If you have additional information on the Sands Fish & Oyster Company, or if you have images to share, please reach out. I will be glad to post an update and provide the appropriate credit.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you click these links and make a purchase, I may receive a small commission. This commission does not affect any price that you pay. Affiliate programs or sponsors providing products do not influence my views and opinions.

The marker can be a bit tricky to find. Use Google Maps to quickly and safely navigate your way to it.

Prior to the first incorporation in 1927, in 1906, local residents F. W. Hatch, H. J. Magruder, and Leonard Mosby formed the Oak Hill Village Improvement Association with goals of organizing community events and resolving any local problems. The Association purchased a lot located at what is now 146 U.S. Highway 1. Here, they constructed a Town Hall building as a meeting space. The building was constructed in a single story octagonal design. The reason this design was created and the name of the architect are lost to time according to the NRHP nomination form.

Prior to the first incorporation in 1927, in 1906, local residents F. W. Hatch, H. J. Magruder, and Leonard Mosby formed the Oak Hill Village Improvement Association with goals of organizing community events and resolving any local problems. The Association purchased a lot located at what is now 146 U.S. Highway 1. Here, they constructed a Town Hall building as a meeting space. The building was constructed in a single story octagonal design. The reason this design was created and the name of the architect are lost to time according to the NRHP nomination form. A park, adjacent to the Hall was dedicated in Dr. Chung’s honor on May 21, 1995. Approximately 100 persons turned out for the ceremony which featured a chorus from Burns-Oak Hill Elementary School and a solo from singer Pat Plummer. A reception in Dr. Chung’s honor was held in the Hall after the park dedication.

A park, adjacent to the Hall was dedicated in Dr. Chung’s honor on May 21, 1995. Approximately 100 persons turned out for the ceremony which featured a chorus from Burns-Oak Hill Elementary School and a solo from singer Pat Plummer. A reception in Dr. Chung’s honor was held in the Hall after the park dedication. Village Improvement Association Hall

Village Improvement Association Hall

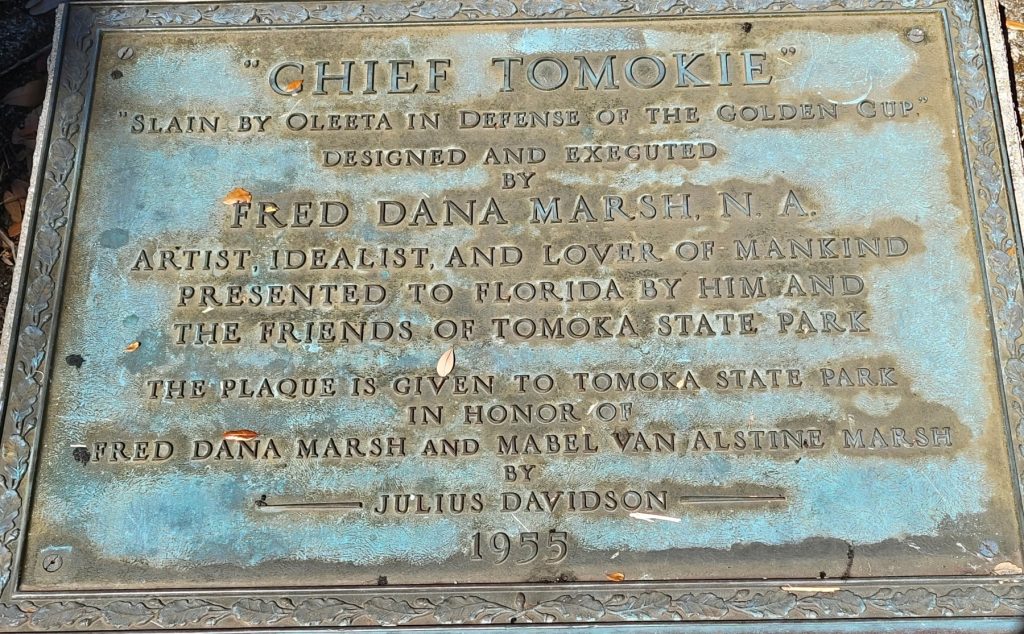

Tomokie Today

Tomokie Today